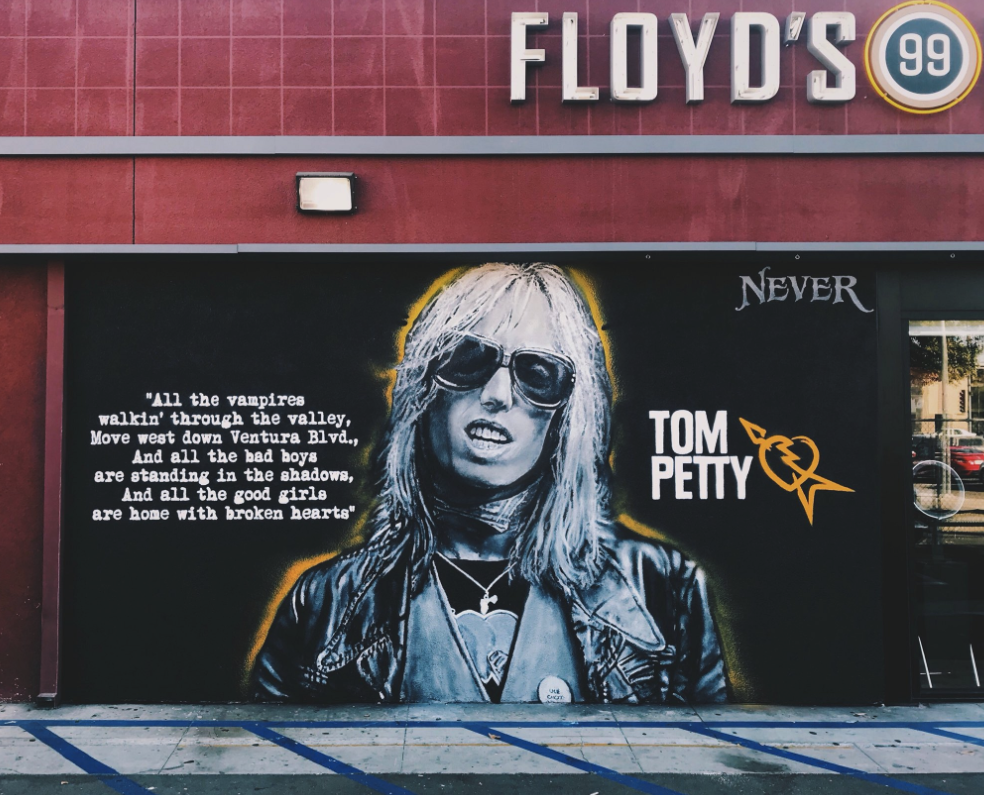

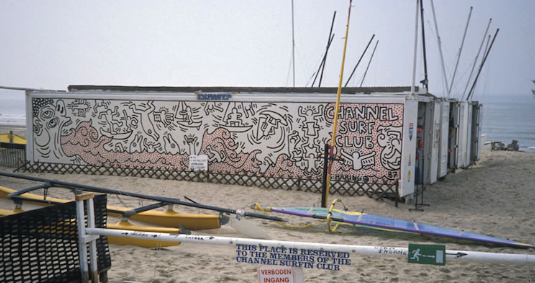

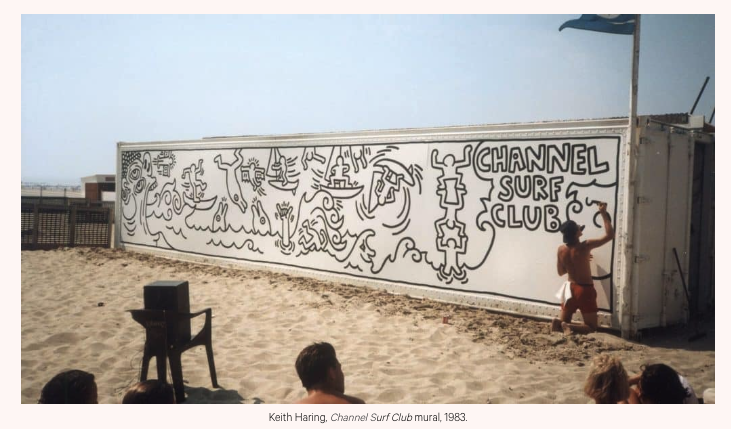

Often I come across some really nice mural

or hand painted sign out there

that I want to share with you!

Here’s another One…

( ...Down Dog that is!)

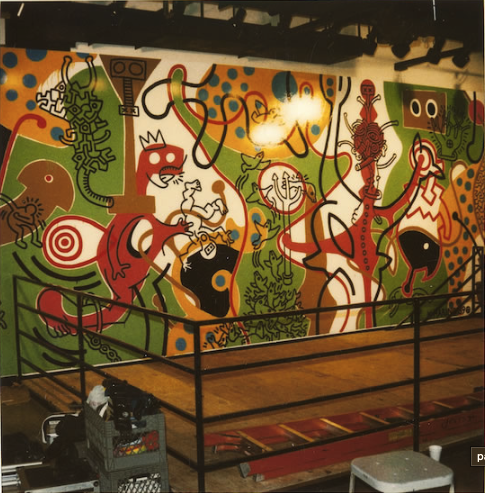

One Down Dog Mural

- By -

J o e r a e l

-Jessica Rosen, Founder One Down Dog

At the heart of Eagle Rock is our second studio, nestled between and convenient to Glendale, Glassell Park, Highland Park and Pasadena, the middle child that we love oh-so-much. Our signature ODD graffiti marks the spot and you’ll find a friendly staff member ready to greet you at the end of a long hallway. If a place could make an expression, our Eagle Rock studio would constantly smile.

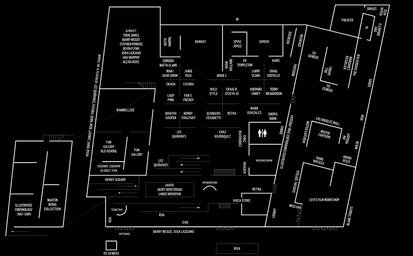

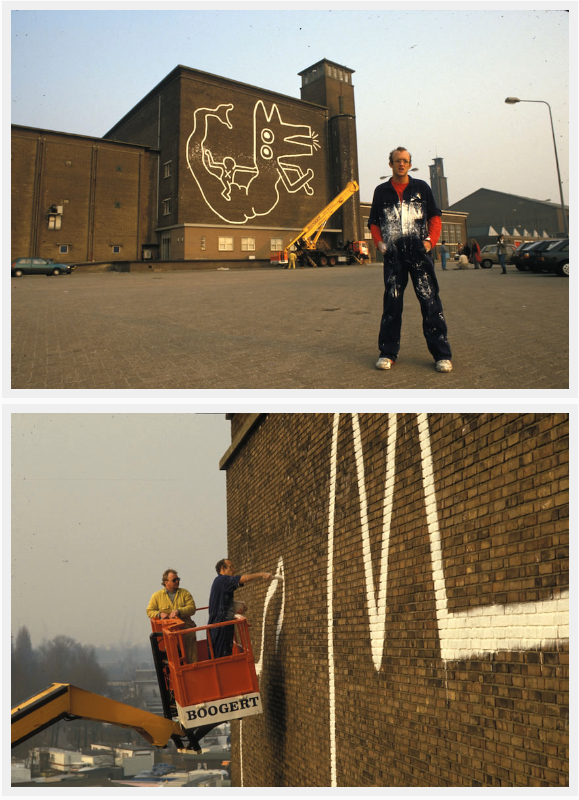

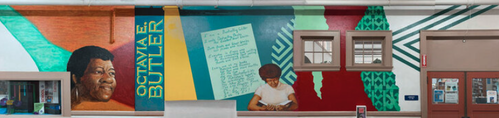

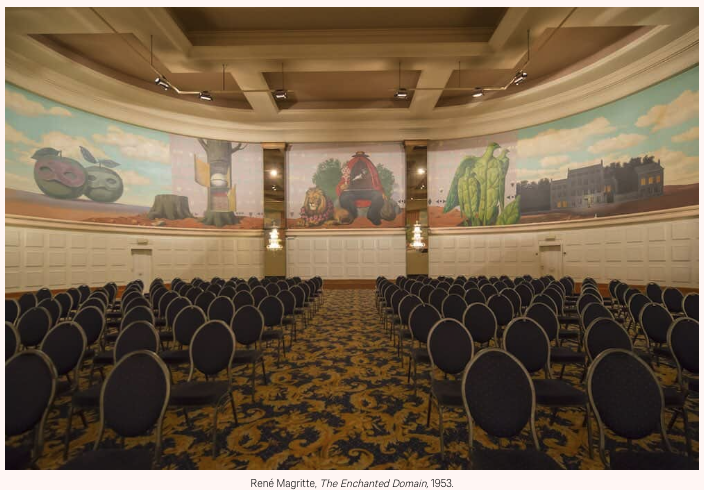

WASHINGTON,DC 2018

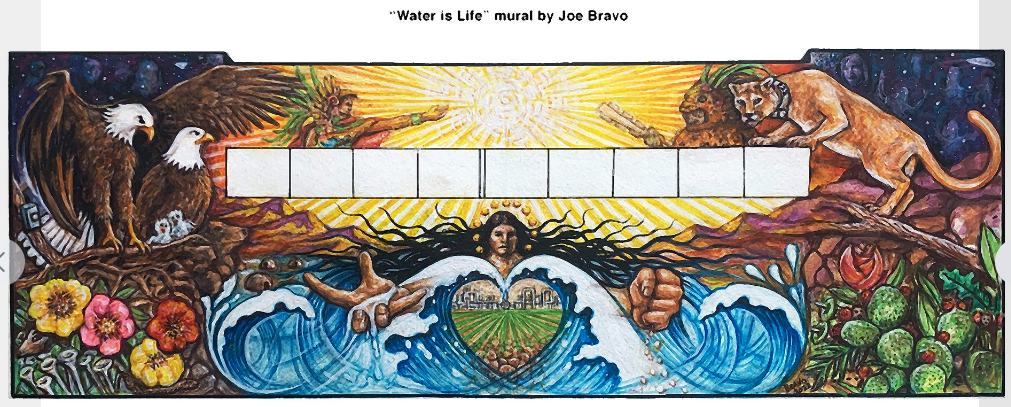

Joerael's epic mural at The Corcoran School of the Arts and Design. This mural spans the length of 2,052 square feet and artistically shares the history of the local Piscataway Tribe.

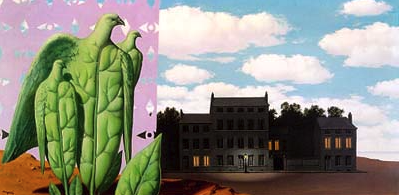

The Piscataway are 'the people where the rivers bend' and call the DC Bay Area their homeland.

Sebi Tayac and Gabrielle Tayac.

Their contributions, time, and stories supported manifesting the mural into reality.

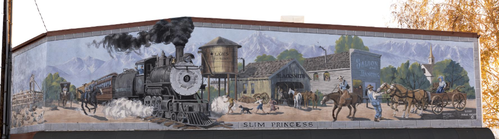

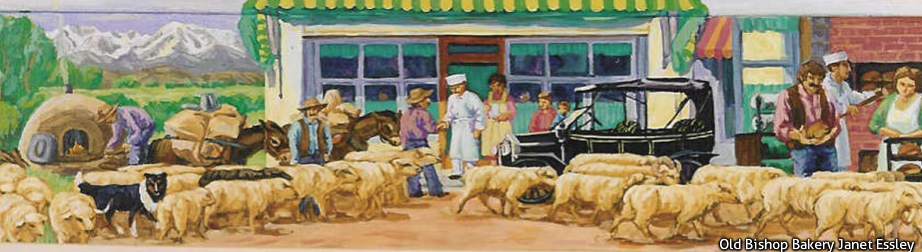

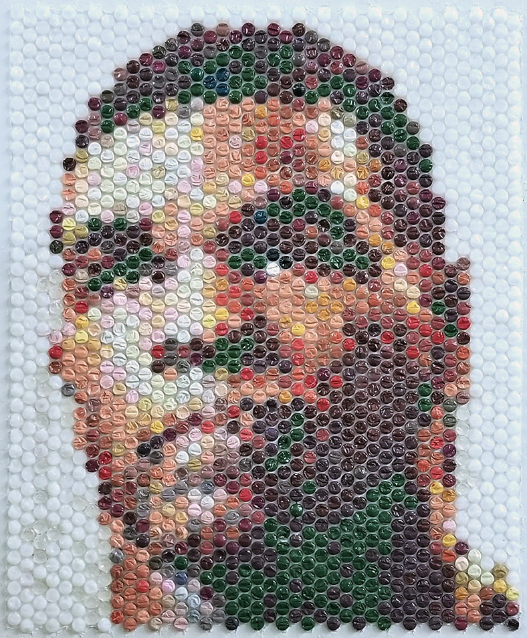

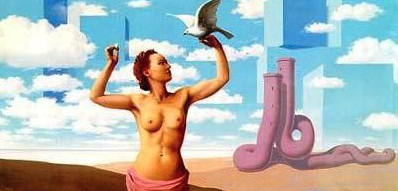

Sky Railway

SANTA FE,NM 2020-2021

photos by Micha Gallegos.

explains Joerael...

“I remember clearly as a boy in San Angelo, Texas, watching on television as the Berlin wall came down, and being captured by the vibrancy and ephemerality of the graffiti, and sensing the transformative effect art can have on a moment in time and the people experiencing it. And that single experience has informed how I approach my role as an artist.”

- JOERAEL NUMINA

RSS Feed

RSS Feed