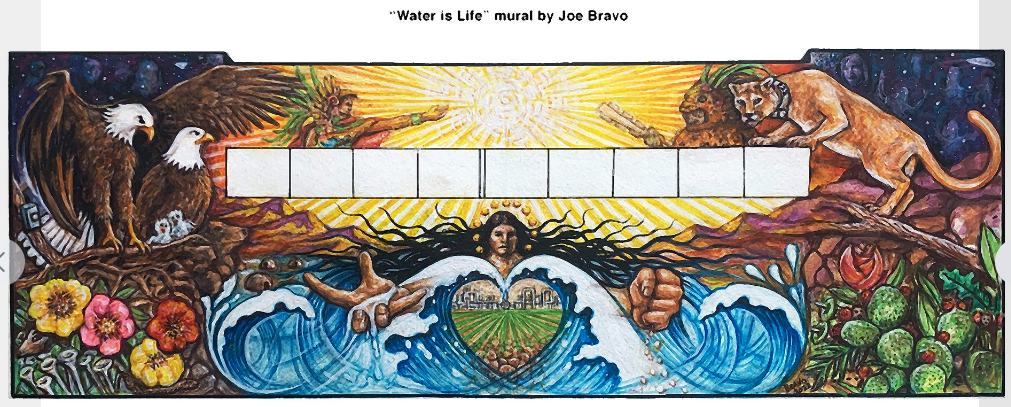

‘Water is Life’

mural in Highland Park a community effort

Bravo found his love for art while growing up in Calexico, California making figurines with mud and swords with scrap wood. Although he is now retired, Bravo continues to use artwork like “Water is Life” to uplift his community.

“Parkside Laundry is perfect because it’s right across from the park,” Bravo said. “Murals are usually on a busy street, or they’re really inaccessible to the viewing public, but here, people can come sit down, have a barbecue and enjoy the artwork. So hopefully it will uplift the community.”

For Bravo, painting murals helps brighten up the concrete community.

“I want it to be a total community involvement, It was a good experience to see different aspects [of] the community [members] who wanted to participate.”

Born in San Jose, California, Bravo grew up in the border town of Calexico and spent his childhood crossing the border to Mexicali, where his tías and cousins lived. As a boy with few toys, he constructed slingshots, wood swords and mud figures to keep himself entertained. He moved to Los Angeles County with his family in the early 1960s and attended junior high and high school in the port town of Wilmington.

In college, Bravo joined the Chicano civil rights movement, which he still calls El Movimiento, a distinction that makes it more of a philosophy than mere history. With pieces and installations that were both dynamic and responsive, he joined the wave of artists that documented what was going on. Bravo also served as graphic artist for the student Chicano newspaper, El Popo (first published in 1970 by students concerned about the lack of a Chicana and Chicano perspective in newspapers) and organized the first Chicano art exhibit at CSUN recognized by the art department.

"I like to think that maybe some of my activism contributed towards the change" at the school, Bravo says. Today, CSUN's Department of Chicana and Chicano Studies is the largest of its kind in the country offering all kinds of art classes while examining the identities that inform Chicana visual expression, creative production and cultural activism.

"I had an art project due and I didn't have the money to buy canvas," Bravo says. He had just finished eating breakfast, and his eyes settled on a bag of corn tortillas sitting on the counter. Bravo painted five tortillas with Mayan codices and assembled a hanging mobile. He passed his final but the mobile crumbled to pieces shortly after an encounter with the Santa Ana winds.

After graduating in 1973 with a bachelor's degree, Bravo worked as a commercial graphic designer, freelanced for various advertising agencies and served as art director for Lowrider magazine. In addition to his graphic work, Bravo also painted murals in the late 1970s as an artist-in-residence for the California Arts Council. Among the pieces he worked on: The Wilhall mural at the Wilmington Recreation Center, restoration of The Great Wall of Los Angeles along the L.A. River, and a mural depicting the history of Highland Park that still stands at an AT&T building in the neighborhood.

This time, Bravo swapped corn for flour tortillas and went bigger: from 13-inch to 28-inch tortillas. Instead of buying them from a local mercado, he got his tortilla canvases custom-made by Tortilleria San Marcos in Boyle Heights. To prepare them, Bravo singes the flour tortillas over an open flame and applies multiple coats of varnish. The process makes them flexible yet sturdy. He reinforces them by adding a final coat of acrylic, and burlap on the back. The burn marks take on a life of their own, inspiring Bravo's designs.

In recent years, Bravo has devoted more attention to his murals, culminating in large pieces of public art that interweave symbolism and social justice. He aims to preserve and tell stories about the community for future generations. You see it in his Highland Park mural, "Water is Life," with images of trees, bald eagles, and nopales with prickly pears. At the center is Toypurina, an indigenous medicine practitioner that led a rebellion against the San Gabriel Mission in 1785. Even the late P-22 makes an appearance.

Although he no longer creates much tortilla art –– aside from the occasional commision and his #TortillaTournament appearances –– Bravo's masa mastery runs deep.

When asked what tortilla he prefers to eat, Bravo says without hesitation, "Corn. I like painting on flour but when it comes to eating –– corn. I just like my maíz. It's in my blood."

- Joe Bravo

The project is sponsored by:

La Plaza de Cultura y Artes,

501 N Main St.

Los Angeles, CA 90012

https://lapca.org/

and

LA Council District 14

Councilman Kevin de Leon

https://councildistrict14.lacity.gov/

and

The Highland Park Neighborhood Council.

https://www.highlandparknc.com/what-is-a-neighborhood-council

RSS Feed

RSS Feed